Collette Scullion and Steve Robertson examine the experience of supervision and its effect on practice from both the supervisee’s and the supervisor’s perspectives.

Authors:

Collette Scullion, a safeguarding children nurse specialist, South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust in Northern Ireland, Lisburn

Steve Robertson, research programme director, University of Sheffield’s Division of Nursing and Midwifery.

Research summary

- Fourteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with health visitors and school nurses from a trust in Northern Ireland on the subject of supervision.

- The value of safeguarding supervision experiences was positively highlighted by all HVs and the two safeguarding children supervisor participants.

- Preparation for supervision using the risk analysis tool was recognised as imperative by all participants.

- Recommendations include the following: consideration should be given regarding aligning the regional nursing safeguarding children supervision documentation to the Signs of Safety approach.

- Consideration should be given to the regional interpretation of the protected time element of three hours by individual organisations for both the supervisee and supervisor.

- Promoting the uptake of peer support mechanisms for both the supervisee and supervisor is required.

- Further exploratory work is required on the current quality assurance process, which is open to individual supervisor interpretation.

INTRODUCTION

The need for structures and systems that support effective safeguarding practice for children has been repeatedly emphasised in UK child death inquiry reports (Munro, 2010; Laming, 2003), and in case management reviews and inspection reports in Northern Ireland (Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety Northern Ireland (DHSSPSNI), 2011a). Such reports highlight the need for robust supervision arrangements and systems to be in place for practitioners who hold specific and ongoing responsibility for safeguarding children. Furthermore, Laming (2003) and Munro (2010) emphasise that high-quality supervision should be constructive, challenging and held within an open and supportive relationship.

Safeguarding children nursing supervision is separate from, but complementary to, other forms of managerial and clinical supervision (DHSSPSNI, 2011a). It offers a specialist professional service from safeguarding children supervisors, which involves providing specialist case management supervision, advice and support to all registered practitioners in their roles of safeguarding children (DHSSPSNI, 2011a).

The process of safeguarding children supervision is underpinned by the principle that every member of staff is accountable for his or her own practice (Health and Social Care Board (HSCB), 2018; NMC, 2015). The supervisor is accountable for the advice they provide and the supervisee is accountable for the actions they take (HSCB, 2018). Effective safeguarding supervision reduces risk to children and young people while identifying their needs (Warren, 2018). Little et al (2018) recommended that safeguarding supervision should be child-focused, include children of concern rather than just those on a child protection plan, and be able to assess risk through challenge and critical reflection (Jarrett and Barlow, 2014).

In Northern Ireland, health visitor and school nurse (SN) practices are shaped and directed by Healthy Child, Healthy Future guidance (DHSSPSNI, 2010) and, where there are identified unmet health needs, enable practitioners to deliver a universal or targeted service to families with babies, pre-school children, school-aged children or adolescents. HVs and SNs, therefore, play a key role in safeguarding children (Littler, 2019). Yet, to date, little research has considered safeguarding children supervision experiences for these professional groups.

STUDY AIMS

- To understand the experiences of safeguarding children supervision from both the supervisees’ (HV and SN) and safeguarding children supervisor’s perspectives.

- To consider how the regional risk analysis tool is used within safeguarding children supervision.

- To consider how the regional risk analysis tool influences the supervisee’s practice.

METHODS

The study used a qualitative design as an appropriate way to ascertain information on people’s understanding and experiences (Meadows, 2003). The aim was to understand more about the HV, SN and safeguarding supervisor experiences of safeguarding children supervision; qualitative approaches are best placed to facilitate this understanding, as they seek to study a phenomenon through people’s own perspective, paying attention to the context within which they emerge (Denzin and Lincoln, 2005).

Recruitment took place via a combined purposive and convenience sampling technique; this was chosen by necessity rather than by design. The aim was to ensure HV and SN diversity across the South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust. A welcome email with a participant information pack was sent to all 85 HVs, SNs and safeguarding children supervisors in the trust, inviting them to take part. HVs, SNs and safeguarding children supervisors are located across three individual areas. The first four participants, plus the one safeguarding children supervisor, in each locality (14 in total) who returned completed intention-to-participate forms were recruited onto the study. The first-named author is a safeguarding children supervisor in one locality, which was therefore not included in this study. Seventeen HVs, and two safeguarding children supervisors, expressed interest. A waiting list was developed for the additional five HVs in the event of participant drop-out (however, this list was not needed as there was no drop-out). HVs had a range of experience, from being a student HV through to a qualified HV with more than 10 years’ experience. Two safeguarding children supervisors had more than 13 years’ experience in the role. No SNs returned the intention-to-participate form.

Ethical approval

Prior to recruitment, ethical approval was sought and obtained from the Ulster University School of Nursing Ethics Filter Committee and the Trust Directorate. Informed consent was obtained from participants before commencing data collection. All participants were assured that names and other identifying data would be made anonymous so that comments could not be directly attributed. Participants were offered a convenient time to complete a Zoom (rather than face-to-face) interview, given the Covid-19 pandemic and the need to minimise inconvenience and travel costs (Grove et al, 2013). This approach was supported by the Ethics Committee.

Data collection

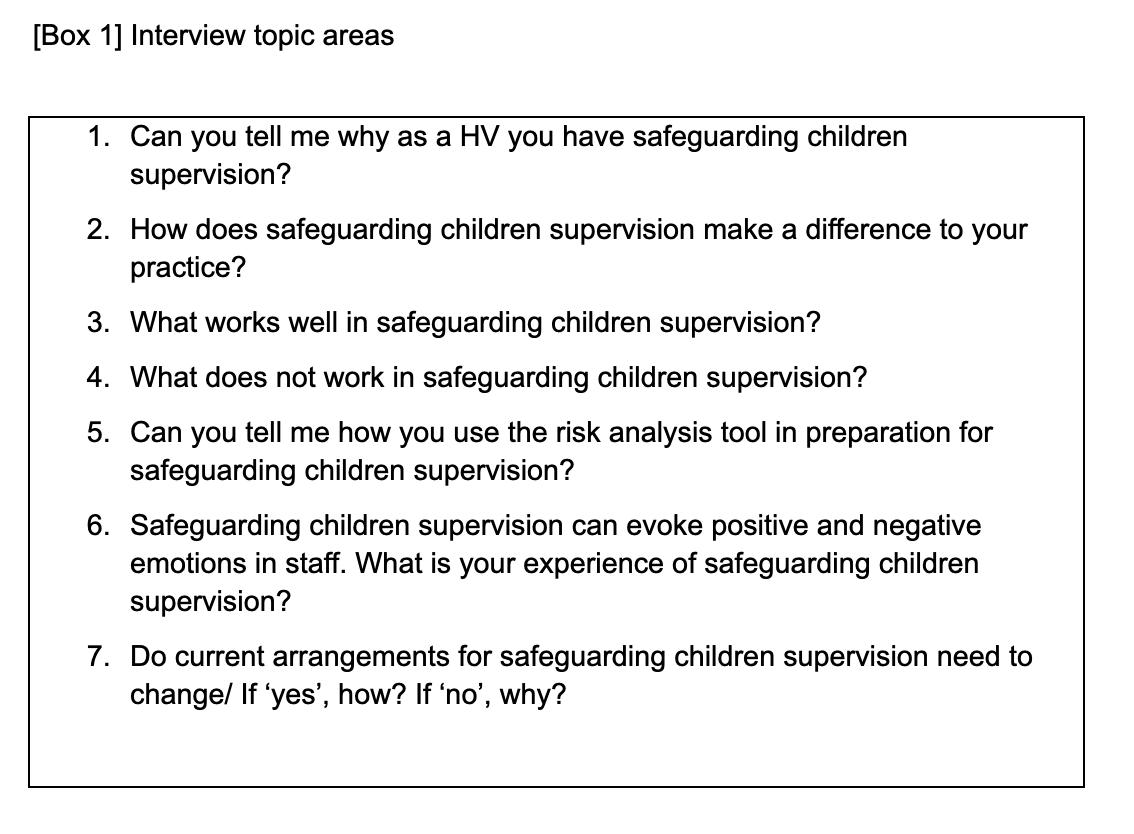

A topic guide (Meadows, 2003), listing areas to be explored during interviews using open-ended questions, was developed (see Interview topic areas below). Fourteen semi-structured interviews, lasting from 30 to 45 minutes, were conducted, and recorded in November 2019. Participants were advised that, while responses would be anonymous, any disclosures of malpractice or adverse incidents would be reported and escalated, in line with university and trust policy and procedures and in accordance with the NMC code (NMC, 2015).

Data analysis

Recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and each participant was given a code, such as ‘HV 1’, ‘HV 2’ and ‘HV 3’, or ‘safeguarding children supervisor 1’. A thematic content analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was employed to analyse the data. An initial coding index was developed and applied to the dataset. Codes were collated into potential themes, and thematic maps were colour-coded for each of the initial themes. The final stage involved charting out key themes, and interpreting and making sense of the data within and across these final themes. Independent code and theme checking took place with another member of the research team.

RESULTS

The thematic content analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) identified three themes and several sub-themes (see Themes and sub-themes below). Direct quotes are used to illustrate the themes, using the participant codes noted earlier. While numbers are not often used when presenting qualitative research, Silverman (2001) suggests they can be useful in providing an indication of the strength of points being made. Some numerical data is therefore also included in the findings section.

Theme 1. The need for supervision

Most participants identified that safeguarding children supervision was fundamental in delivering high-quality health visiting practice to children and families. Responses from all participants showed that supervision was crucial in safeguarding the child and placed the child in the centre of supervision sessions:

‘[Supervision] is of benefit to the children we look after, […] I’m glad it happens, it helps the children, it helps me be a better health visitor and provide a better quality of care’ (HV 6).

In focusing on this theme, participants said that safeguarding children supervision was a key area of practice that supported them in their role and protected them, which then protected the welfare of the child and their families:

‘I want my practice to be as high a standard as possible; […] what we want is quality, effective, safe practice, and the best for protecting children’ (HV 7).

To maintain standards, when individual safeguarding supervision relates to a child or family, client records are audited as part of regional policy. Half of the participants (n=6) positively evaluated such record auditing:

‘I like the fact the safeguarding children supervisor looks at the records. I find that reassuring […], I want my practice to be as high a standard as possible’ (HV 7).

The need for practitioners to discuss worries and concerns in safeguarding children supervision was identified by five participants as a key reason for supervision, with three participants identifying supervision as an opportunity to discuss and progress actions with the supervisor:

‘Having someone to discuss my problems and worries with, […] so my worries can be just nipped in the bud’ (HV 3).

Peer support was highlighted by a small number (four out of 12 HV participants) as happening informally, in unplanned ways, and within everyday interactions with colleagues. However, concerns were raised about such peer support interaction increasing stress levels. Group supervision was deemed non-conducive for some participants:

‘In the office, you are bouncing things off each other and you feed off each other’s stress’ (HV 1).

‘For me [group supervision] doesn’t work – it doesn’t feel like proper supervision, it feels like a tick box exercise that has to be done’ (HV 11).

When experiencing negative emotions such as frustration, worry and stress, three participants described coping mechanisms that ranged from talking to colleagues and sharing feelings to contacting the safeguarding children supervisor for debriefing exercises:

‘Chatting with the safeguarding nurse and reflecting on that with her, it is like you get it off your chest…. like a debriefing’ (HV 6).

Theme 2. The supervision processes

There are various timings and methods used to meet the four functions of supervision (management, education, support, mediation). All participants reported that planned four monthly supervisions were highly effective for supporting safeguarding practice. In addition, three participants made positive comments regarding their experiences of the more intensive induction and then planned four-monthly supervision mechanisms:

‘As a new health visitor, safeguarding supervision was on a monthly basis, which was appropriate for my needs’ (HV 6).

‘I think that three times a year is needed; I would not want to see that changed’ (HV 7).

Open-door advice and support regarding specific child, family or safeguarding issues at the request of the nurse is another method available. This may be a face-to-face consultation or a telephone call. This method was identified as a valuable component of safeguarding supervision by 10 participants:

‘What works well [is] an open-door policy, so they are always available for you to speak to them if you have a query – they are also at the end of a phone or email’ (HV 6).

Usually. three families are discussed in detail, and actions recorded on the record of safeguarding case supervision, during supervision. The importance of preparation for supervision was recognised by all participants. The preparation tool used within the trust was deemed to be of benefit by 10 participants in helping them reflect and maintain focus:

‘You have to prepare to do it properly, […] it is really worthwhile, and I think because we do all take safeguarding children seriously’ (HV 12).

A two-hour window of protected time is permitted to allow HVs to attend supervision. Half of the participants noted that protected time provided an opportunity to reflect on families that practitioners were working with, and to review interventions that were in progress or required for the future. However, seven participants highlighted that there was not sufficient protected time available to complete the required paperwork that forms part of the supervision tool.

‘You’ve got the protected time for the meeting, it isn’t too long and isn’t too short […], so it’s focused, its two hours, and it’s protected’ (HV 9).

‘Sometimes the time constraints of getting the paperwork organised and getting it together […], it is filling in the paperwork and getting it ready to go for your supervision that is time-consuming’ (HV 8).

The modern style of running child protection case conferences, using the Signs of Safety approach, is designed to increase family involvement and the understanding of concerns and risks the professionals involved have for the children (Stanley and Mills, 2014). Over half of HV participants, and the two supervisors, positively evaluated this approach, but further emphasised that the current risk analysis tool needed to be aligned to this approach:

‘We are using the Signs of Safety approach […] what we are concerned about, and what needs to happen, if the supervision paperwork could be married up with this format?’ (HV 3).

The ability of the supervisor to provide different perspectives on situations was appreciated by 10 participants, and trust was highlighted as essential for the supervisee-supervisor relationship to work by two participants. Factors that strengthened supervision processes were as follows: supervisor’s experience (three participants), supervisor being trained in the role (four participants), supervisor’s professionalism (one participant), supervisor’s wealth of knowledge (four participants) and the two-way process (three participants):

‘It gives you more clarity on things, a different person’s’ (HV 1).

‘You do have to have trust in who is supervising you. If you don’t have trust, and you are dependent on their experience, that just wouldn’t work’ (HV 1).

Gaining regular feedback on cases and debriefing sessions was reported as beneficial to the delivery of safe and effective care. It was also reported to be invaluable for participants, especially after they had been involved in a case management review or where a child had been harmed. The need to debrief with the safeguarding children supervisor was described as essential. The importance of receiving feedback was present in nine of the interviews:

‘The feedback from the supervisor is really valuable, it’s just so good’ (HV 7).

Safeguarding supervision was reported by 12 participants to support practitioner learning and developmental needs. Three participants recognised how safeguarding children supervision played a role in addressing poor practice, and was therefore part of a wider issue of accountability. Other positive aspects of supervision highlighted included the following: HVs always learning from supervision, keeping staff up to date, understanding boundaries and baselines for practice, improving practice, and helping identify areas for improvement and therefore training needs.

‘It can highlight there are issues in practice – that’s a positive about supervision’ (HV 2).

Theme 3 The value of supervision experiences:

The safeguarding supervision experience was positively evaluated by all participants, with many participants connecting safeguarding supervision with a positive state of mind:

‘I’ve always come away feeling well supported and feeling […] inspired and encouraged, so mine has definitely been a positive experience’ (HV 12).

‘You feel refreshed, and you think you know what was really worth doing’ (HV 2).

The supervisors’ ability to provide a safe space, a different office space, confidentiality and emotional support was obviously key to these positive experiences. A platform to express and contain emotions was highlighted by all participants, with five highlighting the importance of personal support. Safeguarding supervision was considered by five participants as a vehicle to help reduce HV stress:

‘For me it’s a platform to air, to get things off my chest as well… for me it is my comfort blanket’ (HV 3).

‘Firstly, it reduces stress […] you worry about the safeguarding […], you are really well supported and the safeguarding support you get, you have a whole lot more support than you have in other areas’ (HV 12).

DISCUSSION

The need for supervision

The literature outlines the role safeguarding supervision has in promoting child and practitioner safety (Austin and Holt, 2017; Rooke, 2015; Botham, 2013; Hall, 2007). The findings indicate that all safeguarding children supervisors and HVs were focused on the safety and wellbeing of the child in safeguarding supervision. It was not only seen as critical in safeguarding the child, but also the HV and safeguarding children supervisor participants’ perceived safeguarding supervision as a staff protection, and this ultimately protected the child. All participants noted safeguarding supervision as a key area of practice that supports them in their role and in providing a quality service.

Smikle (2017) reinforced the need to support practitioners in order to ensure they have the confidence to undertake safeguarding work. In this study, safeguarding supervision was recognised as a vehicle to reduce HV stress and provide practitioners with a sense of confidence in their roles.

The supervision processes

Although there is no national guidance on how often safeguarding supervision should be carried out (Hall, 2007), findings indicate that Northern Ireland regional and local policy timings and frequency are well received. Formal planned supervision was identified as a valuable component of safeguarding children, and was reported to be highly effective for supporting HV practices.

While the open-door method was perceived as an imperative aspect of safeguarding supervision by most, a few HV participants expressed some hesitancy regarding a perceived lack of this method. The findings suggest that the regional procedure (DHSSPSNI, 2011b) method of open-door advice and support is working well with those interviewed either face-to-face or by telephone call.

Little et al (2018) and Wallbank and Wonnacott (2015) found that safeguarding supervision helps develop practice by improving practitioners’ reflective skills to achieve greater clarity. Preparation of the regional risk analysis tool (which covers four main areas: child’s developmental needs, parenting capacity, family and environment, and partnership working with parents) was recognised as significant by all participants in this study. The tool was deemed to be advantageous in assisting practitioners to reflect and maintain focus. The findings further suggest that practitioner preparation and supervision sessions are being used as constructive learning opportunities (DHSSPSNI, 2011b: p6).

Existing literature outlines the challenges posed by safeguarding documentation (Guindi and Hassett, 2019; Littler, 2019; Little et al, 2018; Hackett, 2013). Within this trust, safeguarding supervision is booked for a protected timeframe of two hours. While half the HV participants welcomed the two-hour window as an opportunity for reflection, other HVs and one safeguarding children supervisor were concerned about the lack of protected time for completion of the paperwork. This reinforces the need to raise awareness regarding the functions of the three-hour protected time, and for the documentation to be reviewed in alignment with the Signs of Safety approach. In terms of the protected time for the safeguarding children supervisor, this requires further exploration from a regional and local perspective.

Smikle (2017) found the need to manage people with sensitivity and importance of the interplay between supervisee and supervisor. The ability to provide a different perspective on situations, create conditions to enable staff to feel safe, reduce staff stress and anxiety, and display mutual respectful care and support, were all cited as positives by most HVs. The findings also suggest that supervisors are creating safe climate conditions for HVs to examine their practices as they are given opportunities to discuss the personal impact of child protection work.

Receiving feedback was considered to be important for reassuring staff and for benefiting the delivery of safe and effective care. Findings indicate that safeguarding supervision not only supports HV learning and developmental needs but also improves HV practices.

The benefits of one-to-one, peer and group supervision used in combination to provide maximum support to practitioners were identified throughout the literature (Taylor et al, 2017; Rooke, 2015; White, 2008; Hall, 2007). However, only a few participants in the current study mentioned informal peer supervision as a supportive mechanism and as a forum to share feelings. The informal peer supervision challenges cited by this small number of HV participants were associated with the potential for stress levels to be heightened by colleagues. Group supervision in this study was perceived to be of little value, a tick-box exercise, or as not being routinely prioritised. Findings therefore indicate the need for raising the profile of group supervision and the possible benefits of peer support.

The value of supervision experiences

Existing literature suggests a variation in experiences among nurses and managers as to what constituted child protection clinical supervision (Botham, 2013; White, 2008; Lister and Crisp, 2005; Crisp and Lister, 2004). However, the value of the safeguarding supervision experience in this study was positively evaluated by all HV participants.

The ability of supervisors to provide a safe place was positively evaluated by some HV participants. This safe space not only included the provision of a private room and avoidance of interruption, but was also seen as a place to emotionally download. Over half of HV participants perceived safeguarding supervision as a safe place to share complex emotions.

The focus on the child, and capturing their views, has been reinforced throughout serious case reviews where children and young people have died or experienced significant harm and, at the time of their deaths or injury, opportunities to safeguard had been missed (NSPCC, 2015; Ofsted, 2010). In this study, supervision was considered as a vehicle to reduce stress by almost half of the HV participants.

All HV participants felt well supported in their roles regarding safeguarding supervision modes and frequencies. Because of Covid-19 local protocols, safeguarding supervision has recently been conducted virtually via Zoom, which was acknowledged by two HV participants as positive. Further research will be required within this area to evaluate if supervision via Zoom works as well as face-to-face meetings for practitioners.

Implications

To the first-named author’s knowledge, this is the first service evaluation of how current regional arrangements for safeguarding children supervision are implemented and experienced by HVs and supervisors in Northern Ireland. The first-named author has observed variances in HV interpretation of the regional available methods which are available, such as open-door advice, peer support, and protected time. To better understand the implications of these results, future studies could potentially address a regional service evaluation of the safeguarding children supervision service. This would measure and evaluate HV and supervisor experiences, and establish the consistency of approach across the region (see Recommendations below).

Limitations

- As this study was small-scale and was undertaken in only one of the five health and social care organisations in Northern Ireland, the transferability of the findings is limited.

- The sample size and sampling technique are open to criticism in that the HV sample size (n=12) and safeguarding children supervisor sample size was small (n=2).

- The findings relate only to HVs as none of the SNs participated, and their experiences and voices may have been different.

- As the first-named author was a safeguarding children supervisor in one locality, the supervisory relationship between role of researcher and supervisor was considered. As the researcher was implicit in safeguarding the integrity of this study and to demonstrate trustworthiness (Finlay, 2006), the process of reflexivity was incorporated into, and engaged, throughout.

CONCLUSION

The value of safeguarding supervision experiences was positively highlighted by all HVs and the two safeguarding children supervisor participants. Preparation for supervision using the risk analysis tool was recognised as imperative by all participants. It was deemed to be advantageous in helping practitioners reflect and maintain focus, and in positively influencing practice. However, this tool was also perceived to be time-consuming, not aligned to the Signs of Safety Approach, and challenging because of the competing demands of the HV role. Overall, findings demonstrate that formal planned supervision was identified as a valuable component of safeguarding children and as highly effective for supporting HV practices.

References

Austin J, Holt S. (2017) Responding to the support needs of front-line public health nurses who work with vulnerable families and children: a qualitative study. Contemporary Nurse: A Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession 53(5): 524-35.

Botham J. (2013) What constitutes safeguarding children supervision for health visitors and school nurses?. Community Practitioner 86(3): 28-34.

Braun V, Clarke V. (2006) Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist 26(2): 120-23.

Grove SK, Burns N, Gray JR. (2013) The Practice of Nursing Research: Appraisal, Synthesis and Generation of Evidence. Elsevier: Missouri.

Crisp BR, Lister PG. (2004) Child protection and public health: nurses’ responsibilities. Journal of Advanced Nursing 47(6): 656-63.

Denzin N, Lincoln Y. (2005) Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y (eds). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Sage: Thousand Oaks, California.

Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety Northern Ireland (DHSSPSNI). (2011a) Regional policy for Northern Ireland Health and Social Care Trusts. Belfast: DHSSPS.

DHSSPSNI. (2011b) Safeguarding children supervision procedure for nurses. See: bit.ly/3PgPCSZ (accessed 29 November 2022).

DHSSPSNI. (2010) Healthy child, healthy future: a framework for the universal child health promotion programme in Northern Ireland. See: bit.ly/3H8RRFN (accessed 29 November 2022).

Finlay L. (2006) ‘Rigour’ ‘ethical integrity’ or ‘artistry’? Reflexively reviewing criteria for evaluating qualitative research. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 69(7): 319-26.

Guindi A, Hassett A. (2019) Safeguarding supervision: on the front line. Community Practitioner 92(6): 45–9.

Hackett AJ. (2013) The role of the school nurse in child protection. Community Practitioner 86(12): 26-9.

Hall C. (2007) Health visitors’ and school nurses’ perspectives on child protection supervision.